Introduction

I am an assistant coach for the Albany High School mountain biking team. The age difference between the student-athletes and me keeps growing, and my bike isn’t getting any younger, either. In fact, it sports a triple crankset, a technology that has all but disappeared from the mountain bike racing circuit. One of the kids said, “We were trying to imagine you on a modern bike with a one-by, but it just wouldn’t seem right.” So this configuration has, for better or worse, become part of my “personal brand.”

What’s that, you ask? What’s a “one-by”? It’s a crankset with only one chainring, which is what most modern mountain bikes have now, paired with a wide-range cluster of gears in the back (the opposite of the “corn cob” I coveted as a youngster). The problem with the one-by setup is, how do you properly execute the maneuver required for a Big Ring Tale?

I did not coin the term “Big Ring Tale”—at least, I don’t think I did, having used this term since the early ‘80s—but when I googled this phrase just now every single hit was this blog. Suffice to say, “Big Ring Tale” refers to a story of a showdown on bikes, with the climax coming when the hero, just before launching his final, devastating attack, “throws it in the big ring”—that is, shifts into his bike’s higher gear range. But this tale takes place on a climb far too steep for the big ring, which is why we’ll have to make do with a smaller one.

Middle ring tale

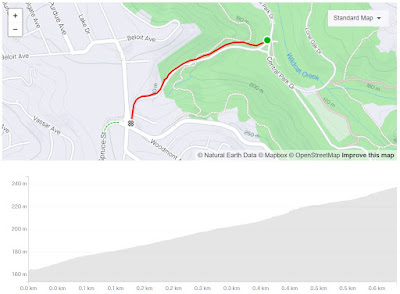

Our team rides are largely on dirt trails, but getting to them and back requires some asphalt. There’s a classic climb we do, on the road, that’s short but very steep. It’s called Canon Drive and it gains 244 feet in 0.39 miles, for an average grade of 11.7%. The top stretch is a fricking wall, topping out at 24.7%! Canon Drive is the last big hurdle we must get over during our weekday rides before descending all the way back to the high school. Most kids hate this climb because we usually have to tackle it when they’re already pretty knackered. They’ll beg for crazy long detours just to get around having to face it; one coach calls this chorus of whining “the ABCs,” for “anything but Canon.”

In my group (only the second fastest, but hey, I’m old!), there’s a kid named S— who is what we call a pocket climber. His physique is just ridiculously spare and lean, his upper body an inverted trapezoid from somewhat aerodynamic shoulders to an ideally narrow waist, and the inevitable “ripped” (i.e., lean) legs. He looks like a Pixar character, someone who could feature in the next “Incredibles” movie or something. On the big climbs I can almost never keep up with him. Today I was hoping he’d be tired enough, this having been a long ride, that I could prevail on this last, beastly climb.

So, I took the front right from the get-go, hoping to perhaps demoralize everyone into just slacking off (being teenagers, after all). I kicked out the hardest pace I could handle, which had my heart into the low 160s, which is over 90% of my maximum heart rate. The wimp that lives in my brain said, “Anyone who can come by me when I’m going this hard deserves to drop me.”

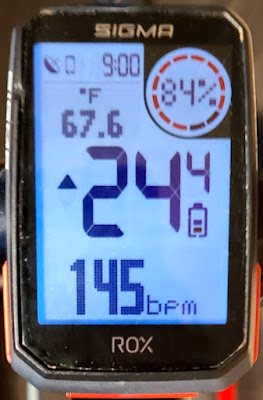

(Obviously the above photo is from a different ride when I had the opportunity to futz with a phone camera. Note the heart rate percent-of-max display, in the upper right, showing 84%, with the “ring of fire” showing in red how close to maxed out I am.)

Notwithstanding this fatalistic sentiment, my self-talk in such cases isn’t all negative. Much of the time I’m simply marveling how high I can get my heart rate when I’m riding with these kids. On no level do I feel like I need to beat them, or that anything is at stake; it’s just that their verve is infectious. Overall think my spirit animal is the cat; that is, I’m kind of a loner. But these team rides bring out my inner sled dog and I can’t help but exuberantly run with the pack, no matter how hard that is.

Soon enough, S—, the pocket climber, as if following a script, came drilling it past me. This was about 5/8 of the way to the top. (Why don’t I just say “about halfway”? Easy for you to say, armchair reader. On a climb like this, practically every foot of every effort is metered out.) S— started to pull away and I thought, “Well, he’s gone, but at least maybe I can hold off Z—.” Z— is the head coach’s kid, who has been putting the hurt on me more and more on every ride, in the process of eventually becoming faster than I, which most of these kids do (and which, let’s face it, is the whole point of coaching them, though it’s a bittersweet experience when they leave you, often literally, in the dust). Sure enough, Z— pulled level a moment later: the next thread in my weave unraveling.

Except it wasn’t Z—! It was this other kid, T—, who is a bit stockier than the others and generally isn’t a factor on the climbs. He’s not naturally built for uphills, perhaps even less than I am, plus he’s pretty new to the sport. Something about how he squares his shoulders, especially when I see him next to a pocket climber, makes me think of Frankenstein’s monster. And, when the hammer goes down, he really thrashes, body rocking all over the place. But here he was, totally going for it, attempting to burst forth and chase S— down, just flying in the face of Fate, despite the iron seeming stone cold!

It was such a cheeky move, so dismissive of the established hierarchy, it inspired me! So I thought, heck, I’m already in the middle ring, which isn’t bad, on a grade this steep, and even though we’d just reached the final wall, where I would normally shift into my largest cog in the back, I thought: what if I just fricking shifted UP, into a harder gear? Or, even, like, two gears up? As in, what if I put the bike in the gear a real man would use here if he were going to lay down a rubber road straight to freedom?!

(Yes, I know in a classic Big Ring Tale I’d be honor-bound to throw her in the big ring at this point, but let’s be real. The grade is more than 20%. I guess I could have taken some liberties and written that I’d been in the little ring, and now threw her in the middle, but that would be false. Could I have called this a “smaller cog” story? No, that just doesn’t make any sense. And one more thing: if “lay down a rubber road straight to freedom” confuses you, you need to go watch “Mad Max” as soon as possible. I believe the expression has to do with accelerating so hard, even when already at highway speed, that you spin the tires and burn rubber.)

Could I really do this? Decide to shift up two gears, and just honor that crazy commitment? Well, my back to the wall, I was just crazy enough to try it. So I stood up (so I’d be standing already when the shift was complete) and clicked the lever twice. My derailleur is pretty bent, so under load it takes a while to shift into a smaller cog, and during this process I kind of lose some power, so mid-shift Z— finally came up next to me, like I’d known he would...

Except it still wasn’t Z—! It was this French kid, G—, the son of a fellow coach who is a brilliant world class physicist living in the US for a while helping America’s best scientists solve some crazy problem using a giant multibillion particle accelerator, but I digress. He (the kid, not the physicist) is normally off the back on these climbs, given the elite group he’s in, but he was having the ride of his life! He had dropped Z— and A— and was about to drop the fricking coach, that being me!

But it was not to be, because suddenly my bike was in gear and I fricking went! I accelerated with astonishing effect and I heard G— make this kind of odd noise, between a sigh and a puff of air bursting from his lungs through his mouth as his dream was instantly scuttled.

Okay, so, at the risk of exhausting your patience with another aside, I need to get something straight here, because when I regale my wife with tales such as this, she doesn’t quite understand the dynamic and to her, these acts of aggression are puzzling, even disconcerting. She ran track in high school but it was mostly a social thing, without much rivalry within the team. But the fact is, high school mountain bikers are just aggressive. Every climb, every descent, heck, even the rare flat section, is an opportunity to thrash your teammates. It’s automatic. It’s not the same as the road teams I was on at their age, where we were on a team with adults who let us ride with them so long as we behaved (i.e. rode predictably). And when we teen roadies went on long rides together, sure, the hammer would go down from time to time, but we also chatted quite a bit, at a casual pace, and at other times relied on each other for a good draft, taking turns facing the wind because it was a long way home. Mountain biking is different. The rides are shorter, more intense, and generally a free-for-all. And as a coach, my job is to lead, inspire, and demonstrate the subtle arts of tactics, psychology, and (when I can manage it) brute force. This isn’t like other team sports where the coach just does a lot of talking from the sidelines. We NICA coaches suffer right along with our student-athletes, on every ride. And, in the faster groups, we coaches pwn these youngsters whenever we can because our window for doing so is slowly but inexorably closing. We know it, and the kids know it: virtually anybody who sticks with the program for all four years can look forward to eventually surpassing the coach. Until that moment, we coaches are all-in, comfortably confident in the knowledge that even the most solid drubbing we can inflict won’t discourage these kids. They look at us: we’re old, we’re oddly fast, but we’re mainly old, and eventually, one day, vengeance is theirs. They will repay. [Insert winking emoticon here.]

Okay, where was I? Ah, yes, I’d completed my brave upshift and launched my quixotic attack. I was drilling it like a madman! Now, as you already know, anybody—even a guy who’s already hammering, even at >90% of his max heart rate—can stomp on the pedals and accelerate for a little while, maybe 50 or 100 feet, before he totally detonates. Such accelerations are impressive until they fizzle. Except that I didn’t! I just felt this crazy surge of power, like a giant wave had just swept me up and was hurtling me toward the beach—except it wasn’t a beach, it was a wall! The ruthless final stretch of Canon Drive! And I was flying!

The pain was so severe it just triggered some altered state where nothing could stop me, and I flew up that hellish pitch with absolutely no regard for the abuse I was inflicting on myself, much less for the laws of gravity. I felt like a squirrel running straight up a tree! It seemed impossible to catch the other two, except that suddenly they were in great difficulty—the difficulty I should have been in, but somehow wasn’t—and I was gaining on them with a quickness!

As I raged up the slope, fate caught up to T— and he detonated, right near the top, less than fifty feet from the prize, and as I overtook him I was in striking range of S—. As we went around the ridiculous corner at the top (where it’s so steep it’s impossible not to peel out in your car after stopping at the stop sign), I squeezed past S— and just nipped him at the line! Or did he nip me? There was no photo-finish camera, but either way, he must have been astonished I was even there, after having been so thoroughly distanced earlier. I looked down at my heart rate monitor, and for the first time ever, I mean in my entire life, it read 100%! So this was kind of a triple-victory! Man vs. Nature, Man vs. Man, and Man vs. Himself! Daaaaaamn!

So was there a victory salute? Applause? A ticker-tape parade? An engraving in some memorial plaque? Of course not: just a fist-bump and a breathless “NOOICE.” Of course in the moment this tête-à-tête felt like kind of a big deal, as in “What a rush!” but it was ultimately just another hill, just another sprint. And when intense, all-in suffering like this becomes routine, that’s when the humble teenager becomes an athlete, ideally for life.

—~—~—~—~—~—~—~—~—

Email me here.

For a complete index of albertnet posts, click here.

No comments:

Post a Comment