Introduction

Some weeks ago, a cycling pal emailed around this article concerning the new Shimano 105 electronic (aka Di2) groupset. I suppose the new 105 release was just a hook, to make the article timely. Most of what the writer focused on was Shimano’s decision to discontinue non-electronic shifting. Surely the point of my teammate’s group email was to kick off a spirited discussion.

Ten years ago, the discussion might have been a lot more lively and long-lived; this group is not shy about expressing themselves, as you can see here. But this time around, though the responses were as insightful and funny as ever, there were only nine of them. I sense we’re gradually tiring of such worldly matters. That said, after some reflection I decided to take the bait—hence this post.

Don’t worry, my thesis isn’t actually as pedestrian as “what’s wrong with Shimano?” but something closer to “is there anything funny, as in ha-ha-funny, about the society that has produced this nonsense from Shimano?” If you don’t get a chuckle out of this post, please be sure to leave a nasty comment below it that will spark an endless, mean-spirited debate sure to propel me from an unseen, unheralded blogger to a global Internet celebrity with my own line of spaghetti sauces and fake Oreos.

In a nutshell

The thoughtful and well-written article, in a column called “Jim’s Tech Talk,” gives four reasons why “it’s a mistake for Shimano to only offer electric shifting road groups.” Jim’s reasons are as follows:

- Higher prices

- [Planned] obsolescence

- Electric derailleurs wear out

- Greater chance of user error

I won’t go into each reason because a) you can read the article yourself—it’s not that long, and b) everything he said seems reasonable and doesn’t warrant a critique. But he missed a couple points, which to me are the most important ones. Those I’ll cover.

Shifting is already easy

First and foremost, modern mechanical shifting is fricking awesome on any halfway legit road bike (and I’ll define “halfway legit” as “Shimano 105 mechanical or equivalent on up, from about 1996 onward”). Electronic shifting is a solution looking for a problem. It’s erroneous to suggest that the ostensibly improved performance justifies the expense (to the extent that we shouldn’t even be given the opportunity to save money on traditional cable-pull gear).

This Shimano 105 Di2 video enumerates the supposed benefits. We’re told Di2 “makes shifting much easier” with “more consistent performance.” Bullshit. Ever since the introduction of Hyperglide cassette cogs and chains, modern chainrings, and indexed shifters, gear shifting has been consistently easy. (Before that, shifting was more difficult but I didn’t care, just like I don’t mind making drip coffee instead of insisting on the brainless ease of a Keurig.) The Shimano 105 promo video says there are “no cables to stretch over time,” but so what? Adjusting cable tension is really easy. You just turn the little barrel adjuster on your derailleur counter-clockwise a quarter turn to see if it gets better. If so, you’re done. If not, turn it half a turn to the right. It’s simple trial and error, and if you don’t even have a bike stand, you can just do it while riding.

(Yes, there is a simpler way to do this. Put the chain on the second-smallest cog, and look at the derailleur pulleys. They should be directly below, or perhaps very slightly to the left, of the cog. A thousand YouTube videos are just waiting to teach you this. Just like there are a thousand videos to teach you how to adjust your electronic shifting.]

But wait, there’s more!

To be fair, the Shimano 105 video’s initial claims are kind of hard to evaluate as they’re pretty subjective. But what really annoys me is that the video goes on to state something that’s plainly untrue, in the most patronizing and degrading language possible:

“Unlike mechanical shifting you can shift under load. Now, that’s a fancy way of saying you can keep pedaling while changing gears. So you can keep going, even on that steep hill.”

I shift under full load all the time. I’m riding Shimano Dura-Ace 9-speed levers that I bought used, over ten years ago, for $100. They’re beat to hell at this point, but still work perfectly. I routinely shift from a smaller cog into a larger one (i.e., the harder type of shift) under full load, while riding out of the saddle, on serious grades like Lomas Cantadas. I’m similarly aggressive with front shifts. I shift under load for fun. I do it because I can. I’m delighted how well it works because I couldn’t do this before about 1997.

And what’s this shit about “shifting under load” being “a fancy way of saying you can keep pedaling while changing gears”? Does the presumed viewer of this video, who’s supposed to drop close to two grand for a 105 Di2 groupset, or spend more than three grand for a 105-Di2-equipped bike, not know what “shift under load” means? And actually, except with internal-geared hubs, don’t cyclists have to keep pedaling while changing gears? And this bit about “you can keep going, even on a steep hill”—what the hell are they even saying? That with mechanical shifting you can’t keep going? You try to shift, it doesn’t work, so you just turn around and find a flatter route home? Or call an Uber?

The video concludes, “The 105 Di2 energizes you. Now there is nothing holding you back.” I got news for you, Shimano: even if mechanical shifting were inferior, poor shifting almost never holds anyone back. When I’m held back, it’s sometimes age that does it, but more often it’s time, because I’m too busy working (so I can afford my disconcertingly expensive lifestyle). And I’m one of the lucky ones. You know what holds a lot of people back? How damned expensive bikes have become. They’re a luxury item now, pretty much by design: companies like Shimano are obviously happy to cater only to the high end customer, and the more ignorant the better.

I wish this were a live demo instead of a video so I could say to the guy, “Wait, hold on. You lost me with that ‘shift under load’ thing. Despite my vast bicycle budget I’m a complete novice.” And then when the Shimano guy happily explained what that “fancy” language means, I could say, “But shifting while pedaling … does that help? Does a bicycle need to be pedaled at all times?” No, he would explain patiently, but pedaling is always necessary when you’re pointed uphill. He’d be all too happy to dumb it down for me because I would seem like the perfect customer: I’m just absolutely shitting money but I’ll never wear anything out or demand a warranty. I’ll just upgrade my fleet in a couple of years despite everything being in mint condition, so I’ll always have the latest and greatest technology, just like with my smartphone.

(Don’t get me wrong, I have nothing against technical innovation and in fact really dig it—when it produces a tangible benefit. I have waxed rhapsodic about Dura-Ace aero wheels, here. And I actually dig Shimano components—I’ve equipped my road and mountain bikes with them for decades. And lest you think I’ve never even tried electronic shifting, I have: click here for a full report.)

Then and now

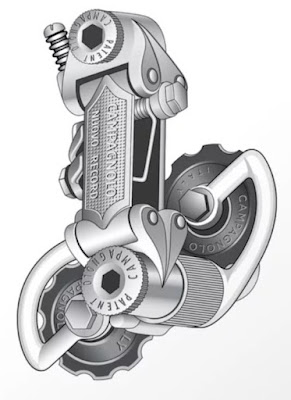

When I started racing, there was no planned obsolescence in bicycle components. My first Campagnolo derailleur, a Nuovo Record, which I bought used (of course), was from 1974. I knew because the year was embossed right on it. The shifting performance was only okay, which was fine, because the derailleur was light, cool looking, and above all durable (e.g., unfazed by crashes). Back then you could open up a Bike Warehouse catalog to the Campy small parts section and order any replacement bit you could want for the component you needed to repair. (This was the mail-order outfit that changed its name to Bike Nashbar because too many people, particularly teenagers, affectionately called it “Bike Whorehouse,” or at least that’s what I’ve always assumed.)

Back then, an aspiring racer could afford the sport since there was lots of used gear out there, because it didn’t wear out. And components weren’t that expensive to begin with. In high school, I could afford great stuff on a paperboy’s salary: in 1985 I bought a brand new full Dura-Ace groupset via mail-order for $400. According to a quick Google search, that’s around $1,000 in today’s dollars, adjusted for inflation. A Dura-Ace Di2 groupset today, meanwhile, costs $4,600 online (and this no longer even includes hubs). That huge price tag isn’t the end of the world, of course, because nobody needs Dura-Ace, but remember: the new entry-level Shimano 105 is now almost two grand … almost twice the inflation-adjusted cost of early Dura-Ace. Yes, of course 105 Di2 shifts better than my 1985 Dura-Ace, but so what? What good does all that technology do for someone who can’t afford to buy it? What middle-class teenager today has an extra two or three grand available for entry level equipment?

Also back then, teenagers racing their bikes on a paperboy’s salary had to learn how to maintain their own bikes. This was doable because the components just weren’t that complicated. It was a great learning opportunity which for many of us led to gainful employment during high school and/or college. Now, with the more advanced designs, it’s a lot harder.

The yuppie problem

Despite many years working in bike shops, I was initially apprehensive about bleeding the hydraulic brakes on my mountain bike. That repair seemed complicated to me in the sense that I actually don’t have much understanding about how these brakes even work. After putting off my hypothetical DIY “learning project” for many weeks, I finally just took my bike to a local shop to have them do it. I was a bit disappointed in myself, sure, but also figured heck, I have money, why not support a local business? But then the mechanic breezily said it’d be $60 per brake caliper, and he could have it done in two weeks. WTF?! $120 for a routine bit of maintenance? That doesn’t sound like a reasonable labor rate designed to give a bike mechanic a living wage. That sounds like kind of a luxury tax based on the supposition that the modern bike customer is a totally helpless, ignorant yuppie with a limitless budget. (Needless to say, I balked, bought some tools and brake fluid, checked out some YouTube DIY videos, and now I do this repair myself. And I’ll even do yours for you, for $30 a caliper.)

The attitude shown by these shops may be the new normal as cycling becomes an increasingly yuppified sport. A teammate of mine, an accomplished racer well acquainted with the art of bike repair, took his bike to a local shop recently to have the bearings replaced in the headset and bottom bracket. He knows how to do the work, but didn’t have the specific tools required. He told the shop that the brand of bearings he’d selected last time didn’t end up lasting very long, and asked what other brands they carried. “Don’t worry, we always source the most appropriate bearings,” they told him. “Just drop your bike off and we’ll go over the whole thing and figure out what it needs.” In other words, “Based on our assumption that you’re totally gullible and unconcerned with how much anything costs, we’ll print our own money by doing all kinds of unnecessary ‘repairs’ that you don’t need to worry your pretty little head about.” (My friend, duly insulted, bailed and bought the tools he needed.)

I want to be clear here: I have no issue with wealthy cycling enthusiasts paying top dollar to bike shops if they don’t feel like getting their hands dirty. But what I cannot stand is the overall effect that the bias towards the high end is having on the industry, which seems to have learned to equate wealth with helplessness. It’s as though they assume money actually strips us of capability, to where we’re at their mercy.

This business model isn’t restricted to the bicycle industry, of course; modern cars are more difficult to work on as well, and increasingly expensive. As this Wall Street Journal article explains, “Detroit has jettisoned many of their lower-priced compact and subcompact cars like the Ford Fiesta and Chevy Cruze that have traditionally been starter cars for young buyers.” Modern auto makers prefer the higher profit margins of higher-end vehicles targeted at wealthier customers. Remind you of anyone?

But wait, things get worse as you go up the luxury scale. As detailed in this article, in some markets BMW is now charging customers a monthly subscription fee to enable their built-in seat warmers. The cars are all outfitted with this feature at the factory, but it’s locked out in software until you pay up. This seems inconceivably greedy and cynical to me. I totally get it that a tech company like Cisco Meraki charges a license fee for the software on their Internet/WiFi products, because they are constantly working to improve the software, making updates to protect against new security threats. But seat warmers are nothing new, are available in virtually every new car built by any company, and don’t require any updates. This subscription fee is BMW saying, “We know you have enough money to just throw it unthinkingly at any obstacle that you bump up against, so we’re cashing in on that. Because we can.”

Reading that article was painful enough … but what really threw me were the reader comments below it, some of which justified and accepted BMW’s business model. It’s as though wealth is actually making these customers stupid; that is, excess discretionary income apparently leads just shrugging and accepting absurd price-gouging behaviors. Another of my teammates, responding to the “Jim’s Tech Talk” article, wrote, “The next step will be Shifting-as-a-Service: $10/month to use your derailleurs. Discount for single chainring.” His irony is closer to reality than he might have thought.

So when I see Shimano throwing itself into this model, where the target customer has gobs of money but doesn’t know what “shift under load” means, I feel a little embarrassed to be part of the sport. A neighbor of mine speaks fondly of his childhood in South America playing soccer in a dirt field with all his friends; their ball didn’t even hold air. I love the idea of kids playing stickball in the street in a big city, or pickup basketball on a public court (never mind if the hoop doesn’t even have a net). And then there’s cycling: wealthy and privileged patrons only, please. And the only tools you’ll need are a trash can and a credit card.

—~—~—~—~—~—~—~—~—

Email me here. For a complete index of albertnet posts,

click here.

No comments:

Post a Comment